Poultry can get sick from various bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens. However, unlike dogs and cats, poultry are considered food animals and hence the types of treatments available are severely limited. For example, there are very strict rules on using antibiotics in poultry that are also considered medically important in humans in order to reduce antimicrobial resistance.

Because of this reality, treating your chickens for an infectious disease can be extremely challenging. Therefore, the optimal goal is to prevent the disease from entering the flock in the first place. By following some basic disease preventive practices before and after the arrival of new flocks or birds, you can reduce the probability of a flock becoming infected as well as the severity and outcome of an infection.

Here we describe the “biggies” (aka the poultry infectious diseases that are the most common and/or the most feared).

Most Common Chicken Diseases:

- Marek's Disease

- Coccidiosis

- Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

- virulent Newcastle Disease (vND)

- Salmonella

- Mycoplasma

Understanding some basics about “the biggies” will provide valuable information on common clinical signs and how to prevent infections in the first place with the goal of keeping your chickens healthy and happy!

#1: Marek's Disease:

Marek’s Disease is a highly contagious (spreadable) viral disease of poultry, especially chickens. Marek’s Disease is known to cause tumors which can lead to paralaysis (among other clinical signs) and death. While there is no treatment, vaccination represents an excellent example of disease control. While Marek’s disease is typically considered a disease of young chickens (clinical signs typically appear between 6-30 weeks of age) older chickens are also susceptible.

Unfortunately, the only way to diagnose Marek’s Disease is via a necropsy by a veterinarian. That being said if you have a young bird (vaccinated or not) that has paralysis it is likely due to Marek’s. While there is no treatment, there are way to prevent Marek’s Disease The two pillars of a good Marek’s Disease prevention program are:

- Follow an effective vaccination program. Vaccines must be administered on the day the chicks hatch or in ovo (embryo inside the egg) during egg incubation in order to be most effective. While vaccination is not perfect, if given correctly the vaccine is highly effective at protecting your chickens against disease. Make sure the feedstore or hatchery you purchase your chicks from vaccinate at day of age. Alternatively, you can vaccinate your own birds at day of age. You can easily purchase vaccine at your feedstore or on-line.

- Remove all feather dander when introducing new chicks or birds to your coop. Because the feather follicles are known to carry the virus, removing the feather dander is a great way to reduce the amount of virus in the environment and hence reduce the overall amount of virus your chickens might be exposed to. This is typically done in your coop before moving any chicks from your brooder to the coop. Vaccinated birds or not vaccinated birds, this is very important!

Below you will see aicture of chicken with paralysis from Marek’s Disease. Photo provided by Dr. Mark Bland from Cutler Associates International. Often owners will confuse the paralysis with “my chicken is not hungry.” There are no treatments and the disease is considered the #1 killer of backyard chickens.

#2: Cocci (i.e. coccidiosis)

Coccidiosis or “avian intestinal coccidiosis” is the overgrowth of any species of the protozoal gastrointestinal parasite, coccidia. These single-celled organisms can thrive in your chickens’ guts, causing diarrhea, anemia, suboptimal growth, and even death. Though coccidiosis typically affects younger chickens due to the natural development of resistance against coccidia with age, it is possible for adults to be affected as well.

Also, if you have a mixed age flock, keep in mind that older birds who aren’t showing symptoms can still be shedding coccidia eggs in their feces, infecting the younger chicks Birds become infected if they ingest coccidia eggs from their environment. These eggs are shed in the feces and can remain viable for months in the environment, including in soil, litter, and feed.

Luckily, prevention of coccidiosis is fairly straightforward. The two pillars of coccidia prevention are:

- Reduce the amount of coccidia in the coop environment: Big picture: Focus on preventing water spillage as the combination of water spillage and chicken feces will create the perfect environment for coccidia which can persist and flourish between your chickens and a suitable environment. Management (aka keeping the soil relatively dry) of the poultry environment (especially the soil around where birds congregate is also important in reducing coccidia loads.

- Use a medicated chick feed like Manna Pro's Chick Starter Grower Medicated Crumbles which reduce the number of harmful protozoa in their gastrointestinal tracts while they develop their natural resistance. If you have reservations about buying medicated chicken feed because of concerns about it containing antibiotics, remember that coccidiostats are not antibiotics and are not a concern with respect to human health. If you still have concerns you can accomplish the same results by focusing on good husbandry as described above.

Coccidia can be diagnosed by your veterinarian. Though fecal samples are a quick way to diagnose coccidia, false negatives are relatively common due to the intermittent shedding of eggs in feces. Therefore, some veterinarians may suggest performing necropsies or multiple fecal samples to definitively diagnose coccidia. Once diagnosed, your veterinarian can prescribe medication to treat your flock.

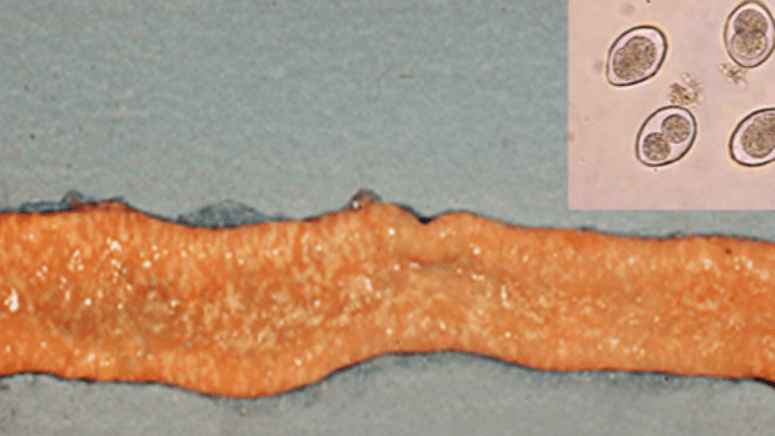

Below is an image of the intestinal tract of a chicken infected with coccida. Microscopic image of coccidia. Gross image courtesy of Dr. Gabriel Sentíes-Cué. Microscopic image from Mike the Chicken Vet.

#3: Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

Globally, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is often considered the most significant poultry disease because of the number of domestic poultry the virus kills annually. Unfortunately right now in 2022 we are dealing with a major HPAI outbreak in North America. As there is no cure and vaccination is not currently an option it is essential for all poultry owners to focus on preventing avian influenza transmission to their flock.

At the most basic level, there are three types of influenza viruses: A, B and C. Influenza B and C do not infect birds but can infect humans. Influenza A can infect humans and many other animals including birds such as domestic poultry.

Wild aquatic birds - particularly certain wild ducks, geese, swans, gulls, shorebirds and terns - are the natural hosts for all known influenza type A viruses. As waterfowl such as ducks and geese migrate south and back again, they have the potential to spread the disease as they interact with other animals including domestic poultry.

Waterfowl are the primary reservoirs of Influenza A. Interestingly most waterfowl are not affected by the virus meaning they don’t get sick as carriers. This means that waterfowl, such as ducks or geese, will appear healthy and continue to migrate all while shedding the virus through their droppings, respiratory secretions.

Consequently, waterfowl are extremely effective global transmitters of the disease. The virus is shed in respiratory and fecal contents. Any contact between infected material and poultry can transmit disease. Hence there is great concern regarding human behavior and biosecurity since humans can unknowingly move virus to domestic poultry by making poor decisions related to biosecurity (e.g. the practice of preventing disease into your backyard farm and flock).

HPAI can cause a range of symptoms that include any or all of the following: inflamed heads with bluish combs, respiratory distress, diarrhea, hemorrhages in the feet or legs, lethargy, reduced feed and water intake or sudden death. In egg-laying hens, a severe drop in egg production and/or soft or misshapen eggs may also be observed.

However, it is important to keep in mind that these symptoms are not pathognomonic, meaning if you observe them in your poultry there are other diseases which also share those same clinical signs. Therefore, if your birds show any of the mentioned symptoms it does not necessarily mean they have HPAI.

The following are highly recommended biosecurity practices for chickens:

- House birds away from open water sources where waterfowl may congregate. If practical, draining ponds to reduce habitat near domestic poultry is recommended.

- Discourage your birds from interacting with wild birds and vice versa by confining your birds to their coop/enclosure. If not possible, consider having a rigorous cleaning routine to prevent your birds from interacting with fomites left behind by wild birds.

- Do not share/exchange animals, equipment or fed with fellow bird owners. At times, restricting access to your birds altogether may be necessary.

- Quarantine new flock additions for 30 days and look for signs of disease before allowing the new birds to join the established flock.

- Frequently monitor your birds and isolate suspect birds right away to prevent the disease from spreading.

- If contact with waterfowl is made, thorough cleaning and disinfection of clothing, shoes and even vehicles used during contact with waterfowl is crucial for preventing the spread of disease onto your farm. If you hunt waterfowl, this is a must follow practice.

- Work with your veterinarian, state/federal veterinarian, local university, farm advisor etc. Many of these resources are free!

#4: virulent Newcastle Disease (vND)

Along with Avian Influenza, vND is considered to be one of the most significant diseases of poultry in the world. While milder strains of vND are somewhat common in North America, the virulent strains (aka vND) are not. However, they do appear periodically and cause significant problems to domestic backyard and commercial poultry.

Because there is no treatment and the disease is highly infectious understanding how the virus spreads is essential to controlling the impact it causes. Specifically, vND can be spread from excretions from infected birds, aerosols and feces. Consequently, the virus can be associated with contaminated feed, water, footwear, clothing, tools, equipment and the environment.

Exposure of susceptible birds to any of these virus sources can result in transmission via inhalation or ingestion. Therefore, it is essential to prevent the virus from spreading to your flock. The best tool we have for that type of control is biosecurity which means practice good husbandry in order to prevent infectious diseases from infecting your flock.

In addition to focusing on biosecurity and management, vaccination should be considered for backyard flocks especially flocks that are in close proximity to affected flocks. However, vaccines are not a "bandaid" for poor management.

Vaccinations such as the LaSota and the B1 vaccine are available at many feedstores for Newcastle Disease. For the LaSota vaccine your chickens may have respiratory signs after the vaccination (this can be a normal part of the vaccine response). The pros of this vaccine typically include a decrease in clinical signs, virus shedding, and spreading this disease. The cons involve the possibility of the virus continuing to spread and be maintained in some vaccinated flocks. This is because the vaccine protects against disease but doesn’t prevent your chickens from getting infected with vND.

#5: Salmonella

Salmonella is a species of bacteria that lives in the gut of many animals and can cause GI problems. Food poisoning from Salmonella can be associated with all kinds of different foods. However, poultry is the most commonly linked food associated with Salmonella.

It is important to understand that some types of Salmonella make you sick and some types don’t. In addition, some types of Salmonella make chickens sick and some don’t… Unfortunately, the ones that make chickens sick don’t often make humans sick and the ones that make us humans sick often don’t make chickens sick. This makes food safety difficult b/c if the Salmonella that made us sick also made chickens sick we could easily remove the sick chickens from the food supply but it doesn’t typically work that way…

So although you are never taught to assume things, in this situation it is probably best from a food safety perspective to assume your chickens are carriers of Salmonella (aka the kind that makes you sick but doesn’t make your chickens sick). This is particularly important if you have children or immunocompromised folks in your household.

How can you determine whether or not your chickens have Salmonella?

- Option 1: send a drag swab (sterile swab) of your poultry environment (see link below) to your friendly diagnostic lab to test out what Salmonella are present…The link for one way to collect this sample will be provided at the end of this video

- Option 2: your second choice is when a bird in your flock inevitably dies you can submit the bird to a diagnostic lab for a chicken autopsy where they can test for Salmonella

Big picture, if the tests come back negative or positive it’s best to assume that your chickens have Salmonella and other bacteria that can cause human illness. Regardless of what information you seek and regardless of the results cook all poultry eggs and meat to 165 degrees Fahrenheit.

In summary, err on the side of caution. Assume your chickens are carriers. Don’t be that guy or girl on the internet that kisses your chicken or that uses the same apron when cooking and when holding their chickens!!!! Not a good thing…

How to Test for Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) in Your Backyard Coop:

Drag-swab Procedure

Background: Salmonella is type of bacteria commonly found in poultry. However, Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) is a specific type of Salmonella that can cause foodborne illness in humans while showing no signs of disease in poultry. Therefore, commercial poultry farms in the U.S. above 3,000 laying hens are required by law to test the environment that their birds are raised in for the presence of SE. The following is a procedure on how to test for SE in your backyard flock. Testing one-two times a year will give you some indication of any risk associated with SE in your laying hens.

Materials Needed: Note: You can find many of these supplies at your local pharmacy or via amazon.

- Whirl Pak© bags (sterile bag)

- Pre-sterilized 4x4 gauze pads (swabs)

- Canned evaporated milk (regular, skim or low-fat)

- Sterile gloves

- Disinfecting wipes with 70% ethanol

- Drag-swab pole assembly (see photo):

- 4ft metal dowel (metal is easy to disinfect)

- Hose clamp

- Alligator clip

- Position alligator clip at one end of the dowel and use the hose clamp to keep the clip in place on the dowel

Preparing the Drag-swabs for Testing:

Wear sterile gloves when handling and moistening the swabs. Always handle drag swabs at edges.

- Disinfect the top of the can of evaporated milk, can opener, and swab poles with disinfecting wipes.You may place a sterile swab over the opened can to prevent flies from contaminating the milk.

- Place clean swabs into individual sterile bags and label them appropriately. The number of samples varies depending on the size of your poultry house (see section below for details).

- Pour approximately 15ml of evaporated milk into each bag to moisten the swab, and squeeze out any excess liquid.

Testing your backyard flock:

- Take one swab and place on the alligator clip and “zig zag” around your coop preferably where there are feces.

- Put the swab in a sterile bag and store at 4˚C (refrigerator temperature).

- Submit the sample to your local diagnostic lab

#6: Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma is a very challenging disease for backyard poultry owners and people who have breeding flocks because the only way to eliminate it with 100% certainty is via 1. culling or 2. testing and culling of breeding hens. Many responsible poultry owners get a diagnosis and then are confused on what they “should do.” This is in part due to the reality that Mycoplasma is considered somewhat ubiquitous in backyard flocks.

Hence, if you test your birds and they come back positive can you assume that all backyard poultry are already positive and therefore you are “OK going to a poultry show or selling your birds?” From my perspective, although you went the extra mile testing, you still have one more step which is to not take sick birds to shows and to communicate your results with others who may be potentially affected.

In general, infections from Mycoplasma cause significant acute and chronic respiratory disease (i.e. coughing, sneezing, sinus infections, ocular and nasal discharge) and “secondary” problems including swollen and infected joints in the hock and foot pad, skeletal deformities, weakness, poor laying and embryo mortalities.

While the clinical signs listed above are often seen in Mycoplasma positive poultry you can’t assume that if you see those signs that your birds have a Mycoplasma infection. This is because other infectious diseases have similar clinical signs in poultry include Infectious coryza, fowl cholera, Newcastle Disease, and Infectious Bronchitis.

In fact, the only way to know for sure what disease your birds may or may not have is via diagnostic testing. Diagnostic testing for Mycoplasma can be done while the birds are alive (i.e. ante-mortem testing) or once they are dead (i.e. post-mortem testing).

While infected birds can be treated with antibiotics by injection and/or in the feed, the treatment is not considered reliable in completely eliminating Mycoplasma but can be a potential option for an owner who does not want to cull infected carriers or flocks.

In addition, because the bacteria can be transmitted from the hen to the chick, if you have sick chicks you need to also test the breeding flock to confirm they are not infectious. In summary while Mycoplasma doesn’t kill a lot of birds, it is highly infectious and very common in backyard birds. Good biosecurity is a must if you hope to prevent it from affecting your flock.

In order to definitively diagnose Mycoplasma in a live bird, a sterile cotton swab is inserted past the mouth into the trachea to recover some of the tracheal exudate. Please work with your veterinarian to obtain proper samples.

Below you will see an image of Sinusitis (i.e. inflamed and infected sinus(es) in a turkey infected with Mycoplasma.